Catamaran Sailing Catamaran Pictures Catamaran Sailing T-Shirts

|

The U.S. Coast Guard A visit to the Station at Channel Islands Harbor By Bill Mattson Now and then, I get a chance to sail out of Channel Islands harbor in Port Hueneme, California. (About 50 miles north of Los Angeles). I always admired the clean, well kept Coast Guard boats stationed there as a sailed by. I recently had the opportunity to visit this station, and was given a guided tour by Petty Officer Shaun Darrall, and Petty Officer Mark Riedlinger.  82' Point Carrew, 44' Motor Life Boat, and 41' Utility Boat (Left to Right) Initially, I had planned on touring the facility on Memorial Day. The station was a bit busy that weekend, however, due to the heavy boat traffic and the usual problems that come with “festivities”. The following weekend was a bit more relaxed, and my son and I dropped by for a look around. |

| Our tour started at a “command center” of sorts, which was located on the top floor, with a nice view of the harbor. A large array of radio equipment filled the room, including a device which actually detected the direction of radio signals. Initially, distress calls are handled by Group Long Beach which is located in San Pedro. They handle the radio calls and dispatch Coast Guard resources as required. These resources include those at Long Beach and Channel Islands, including the large “82 footers”. |

|

|

Most calls handled by the Channel Islands station are sailors who are lost, fatigued, or whose

boats are disabled. Interestingly, many calls involve sailboats whose skipper always runs under

engine power, has run out of fuel, and is not familiar with the sails. “We came across one guy

who was out of gas, and had managed to get only the jib up about halfway”, explained Mark.

And those who are running under sail sometimes get stranded in the afternoon when the wind

dies, or worse: end up in gale force winds. Both imply an inexperience or ignorance of weather

conditions. A common occurrence in the Santa Barbara Channel is fog which develops rapidly.

Given the right conditions, you won’t even see it roll in, as it will develop right on the water.

Other emergencies involve swimmers in riptides, and divers with bad air or getting caught in

kelp. The really dramatic emergencies, namely sinkings and fires, are only encountered about 3

or 4 times a year by the Channel Islands station.

Weekends in the spring are one of the busiest times, since there are many boats on the water that have mechanical problems after sitting all winter. While the Coast Guard may come to the aid of a disabled vessel, they have a policy against taking business away from a commercial business capable of providing assistance for a fee. These assistance operations are closely monitored, however, and the Coast Guard will intercede at the first sign of trouble. Sometimes, communications problems or elderly boat owners will warrant action. One important point raised by my guides was that you should feel free to contact the Coast Guard in the event that you feel a problem is imminent. In this situation, one may feel reluctant to do so, picturing 3 or 4 cruisers with helicopters dispatched! But both Mark and Shaun stressed that you can be more safe than sorry by making this call. The Coast Guard will determine your location, and monitor your situation. They will even put you on a “time schedule” and radio you at predetermined intervals. While you may feel that you don’t need immediate help in some situations, it’s nice to know you’re being watched when things are doubtful Besides, it increases the chances of getting help right away should you reach that point. And if you don’t already own a VHF marine radio, consider one if you plan sailing large bodies of water. According to Mark and Shawn, FCC licenses are no longer required for non-commercial use of marine VHF radios. If you are considering a cellular phone as an emergency communications device, forget it. Rather than broadcast a distress signal to multiple parties, you are restricted to only one. Moreover, the Coast Guard cannot obtain a bearing on a cellular phone transmission. So if you are lost, you won’t be found very easily using a cell phone. |

|

On our way to take a look at the boats, we passed the armory. The weapons stored here

included M60s, M16s and 9 millimeters. Coast Guard personnel are armed on all law

enforcement missions, including routine boat inspections. “You really never know what you are

getting into.” commented Shaun.

The first boat we saw was the Rigid Hull Inflatable (RHI). Capable of 35kts, this vessel is used for short range, fast response missions. The soft sides are ideal for boarding purposes, therefore the boat is used for law enforcement/inspection purposes. Near the RHI was a small training vessel. This boat can be used to simulate rescue situations, and can be flooded, or even set afire using the fire pit near the stern. I figure that if Frank ever joined the Coast Guard, this would be his boat. |

Rigid Hull Inflatable (RHI)  Training Boat

Training Boat |

| Next we were taken aboard the 41’ utility boat. This is a multimission boat, usually crewed by 4. Although of considerable size (36,000 lb. displacement), the boat is capable of 26kts, thanks to a planing hull and twin 318 hp Cummings diesels. The boat can easily handle 30kt winds and 8ft seas. Additionally, it can tow 75ft vessels weighing up to 100 tons. In the case of a sinking vessel, a “dewatering pump” can move 200 gallons per minute. If the situation warrants, the fire fighting pump can also be used for a total pumping capability of 400 gpm. |

The bridge of the 41' Utility Boat |

The 44' Motor Life Boat |

One of 9 watertight compartments on the 44' |

|

In the next slip, we boarded the 44’ motor life boat. While its 12kt speed does not compare to

that of the utility boat, this one is a virtual “tank” in heavy seas. Acceptable conditions to this

vessel include 30 ft seas, 50 kt winds and 20 ft breaking surf. Mark displayed a lifebelt which

can be worn by crew members. “There are “D” rings all over the boat to snap onto”, he

explained. Indeed we did see a few of the rings on the bridge. 2000 lbs of weights are racked in

the lower hull to prevent rollovers. And even in the case that the boat does go upside down, it is

equipped with 9 watertight compartments, each one with padded interior surfaces. . “That might

look like a mistake, but it’s not.”, Mark commented while pointing to an “Exit” sign mounted

upside down on a door. Apparently, when the boat is upside down the sign makes more sense.

A radio and phone is available below deck, in case the bridge is underwater "below".

Also docked at the station was the 82’ rescue cutter Point Carrew. This large vessel is at sea for 7 to 10 days, and patrols from the Mexican Border to San Francisco. Unlike the other boats, this craft is crewed 24 hours a day. But very much like the other boats, it was in immaculate condition. |

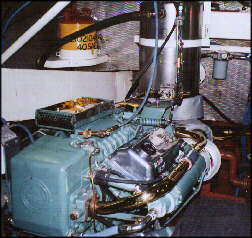

When looks OK, you're having a bad day.  Shipshape engine room on the 44' |

|

I hope I never need the assistance of the Coast Guard, but it’s good to know they are there if I

ever do. It really impresses me that the crews are willing to take these vessels, and themselves,

into conditions others are trying to escape from. And it appears they are ready for anything,

considering the weaponry, fire fighting hardware, stretchers, towing winches and water pumps to

name a few. “Out there, we’re the cops, the paramedics, the firemen, the DEA, and the

immigration department.”, commented Shaun. “We have to be. We’re the only ones out there.”

Bill Mattson mattson@earthlink.net Special Thanks to Petty Officer Shaun Darrall and Petty Officer Mark Riedlinger for their patience and courtesy in providing the tour, as well as their dedication and courage to make our seas safe. Back to Features |